Do you want to live to 100? Does your answer depend on how you will live? Perhaps it’s more important to you to be healthy, active, independent and able to live with dignity than that you live to a ripe, old age — quality over quantity.

Of course, there’s probably a correlation between health and longevity, with those who are healthier also living longer on average. But how much of this is in our control? In other words, how much of health and longevity are the result of healthy living and quality medical care and how much are they simply due to genes and luck?

So, what can we do to improve our healthy longevity, what researchers are now calling “health span,” whether individually or as a society? It’s much easier to answer the second part of the question than the first, partly because there’s so much we’re not doing and partly because the healthy benefits of various activities are often hard to decipher or they’re averages. For instance, we know that there’s a correlation between obesity and bad health, but we also all know about thin joggers who die of cancer or heart attacks and overweight people who live long, healthy lives.

Further, when studies reveal correlations between healthy living habits and either health or longevity, it’s hard to know which ways the arrows point. Are people healthier because they’re more active or more active because they’re healthier? And should we act individually or on a whole society basis, or both?

Longer Life Through Science

There’s now a cottage industry of people, often billionaires, working to find the elixir for a long life. One well-funded company pursuing aging research is Altos Labs, whose “mission is to restore cell health and resilience through cellular rejuvenation programming to reverse disease, injury, and the disabilities that can occur throughout life.” It’s partly funded by venture capital billionaire Robert Nelsen and includes Nobel Prize winners David Baltimore and Jennifer Doudna on its board of directors.

David A. Sinclair, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and co-director of the Paul F. Glenn Laboratories for the Biological Mechanisms of Aging, believes there is no limit to human lifespan. He is the author of Lifespan: Why We Age – and Why We Don't Have To which explains how to delay the aging of our cells, including intermittent fasting, exercise, and supplements.

He argues in an academic article in Nature that focusing research on aging will produce better results, more bang for the buck, than research on cures for specific diseases. He and his co-authors compare the economic benefit, in terms of what people would pay for, of a longer life and a longer health span. “In many ways” they say, “treatments that target aging are more similar to drugs that save lives at younger ages and promote longer spells of healthy life, rather than treatments aimed at extending lifespan for shorter periods of time in poor health.”

As she reported in The Boston Globe, health reporter Carey Goldberg audited a course at Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole about the latest science on aging funded by crypto entrepreneur James Fickel. She learned that the approach to longevity and health span research is to understand how aging affects over all health and how it may be delayed or reversed. Most health care research up until now has focused instead on how to cure individual diseases.

What We Can Do as Individuals

An article in The New York Times reports that experts estimate that 40% of dementia cases can be prevented or delayed by a combination of exercise, good sleep and a so-called “MIND” diet. “MIND” stands for Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay. Both the DASH and Mediterranean diets focus on eating vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fish, poultry, beans, nuts and vegetable oils and avoiding sugars, fatty meat, foods that are high in saturated fats, and coconut and palm oils.

According to the article, the science is still out on whether these practices directly benefit the brain or the cognitive benefits are secondary to the health benefits of exercise, sleep and a healthy diet. If they help control diabetes and stress and improve cardiovascular health, then they will also improve the mind, especially if these practices are followed over long periods of time.

But what’s the benefit of a longer life if its not a healthy life? The care crisis we’re going to be facing in about 10 years as the oldest baby boomers reach their late 80s will not be solved by living longer with dementia and disabilities. It could be solved, at least in part, by improving cognitive and physical health.

Longevity Inequality

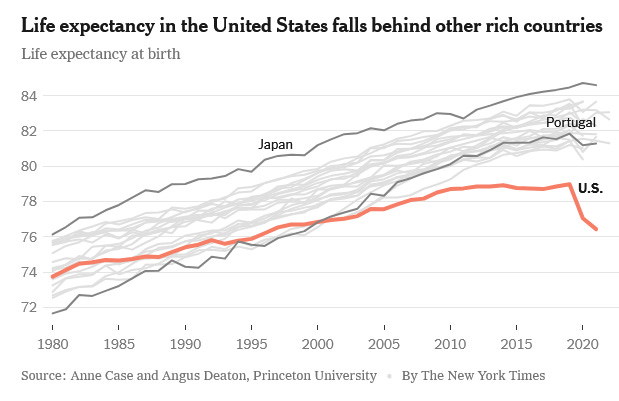

The United States trails most other rich nations in terms of average longevity. In fact, since 2010, longevity in the United States has flattened out and since the pandemic it has fallen.

The decline in life expectancy as a result of the increase in obesity in the United States was predicted as early as 2005. The World Health Organization measures healthy life expectancy (HALE) at age 60 for all countries around world. In 2019, HALE ranged from 10.8 years in Afghanistan to 17.9 years in Austria, to 18.7 years in Costa Rica and 19.7 in France. The United States trailed other developed nations with a HALE of 16.4 years. (Only Lesotho in Africa was in the single digits at 9.8 years.) Where the United States seems to differ most from comparable countries is in the area of “drug use disorders,” which is the top cause of death and disability. It ranks as the 22nd cause in Austria, 26th in Belgium and 4th in Canada. As a risk factor driving death and disability in the United States, drug use increased eightfold between 2009 and 2019.

This is consistent with the class differences in longevity and health span in the United States which the Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton introduced in their book, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. More recently in a column in The New York Times they describe the growing gap between those with and without a college education. According to their analysis of public health records, before the Covid -19 pandemic, 25-year-olds with a college degree could expect to live seven years longer than those without a college degree. Since the pandemic, the discrepancy has grown to eight and a half years.

These differences in health and longevity parallel the increased inequality in income and wealth we have experienced since 1980. According to one study, the “gap in life expectancy between the richest 1% and poorest 1% of individuals was 14.6 years for men and 10.1 years for women” and the gap increased from 2001 to 2014. The reality is that the wealthy and college educated in the United States live as long as their peers in other developed nations in Europe and Asia. It’s the non-college educated and those with less income and wealth who are increasingly falling behind.

Where Should We Invest Our Resources?

So in our world today we have the reality of declining longevity and health span for most Americans at the same time the more well off are living longer and healthier and the billionaires are trying to figure out how to live forever. I question all the energy and bullion being spent on aging research when we’re not taking the steps we already know will increase longevity and life span for many millions of Americans. Before we invest billions in aging research, let’s address the inequality that leads to bad health and low life expectancy. In other words, let’s invest in longevity for everyone before longevity for the few who can afford celebrity doctors and expensive new medical treatments (especially since the verdict is still out on their efficacy).